Insights and Resources

Stay informed with our curated selection of riveting content, keeping you at the forefront of market trends and developments.

Get in touch

Europe’s Water Deficit: Why Old Solutions Won’t Work

Europe’s New Hydrological Baseline: The Invisible Shift

Spain’s renewable freshwater resources per capita have declined by 65% since the 1960s. Malta has lost 54%. Cyprus, 32%. These aren’t temporary dips—they mark a permanent restructuring of Europe’s water cycle.

For decades, European water management rested on one implicit assumption: that rain and snowmelt would continue replenishing rivers, aquifers, and reservoirs at roughly predictable rates. That assumption is dead. The hydrological baseline—the amount of water naturally available in a given region over time—has fundamentally shifted. Three interlocking changes have rewritten the rules. Alpine and Pyrenean snowpack—the natural reservoirs that historically released water gradually through spring and summer—is vanishing. Precipitation patterns have become erratic, with longer dry spells punctuated by intense storms that generate runoff rather than infiltration. Rising temperatures have increased evapotranspiration rates, meaning more water evaporates from soil and vegetation before it can recharge groundwater systems.

Less water enters the natural cycle, and what does arrive is distributed more unevenly in time and space. This isn’t drought in the traditional sense—a temporary deviation that will eventually correct itself. This is the new baseline, and we need to stop managing for a climate that no longer exists.

The Economic Impact: A Triple Whammy

Water scarcity isn’t an abstract future threat—it’s already reshaping how Europe does business. A barge operator in Rotterdam recently said his company now plans routes three months in advance based on Rhine water level forecasts, something unthinkable a decade ago. This kind of operational adaptation signals a deeper shift: water has moved from an abundant backdrop to an active constraint.

The costs show up across three critical sectors, though they often hide in aggregate statistics until a crisis exposes them.

The Rhine carries approximately 300 million tons of cargo annually—chemicals, coal, petroleum, and containerized goods moving between Rotterdam and industrial heartlands in Germany and Switzerland. In 2018 and again in 2022, sustained low water forced vessels to reduce cargo loads by up to 75%, effectively quadrupling per-ton shipping costs. Delivery delays cascaded from steel production to automotive manufacturing, demonstrating how a hydrological constraint can unravel interconnected industrial systems.

Energy generation faces pressure from both sides. Hydroelectric facilities experience increasing volatility as reservoir levels swing more dramatically year to year. But thermal power plants—nuclear, coal, gas-fired—require vast quantities of cooling water. During summer 2022, France granted temporary exemptions allowing nuclear plants to discharge warmer water into rivers, skirting environmental rules to keep the lights on. Several reactors still had to reduce output or shut down. Germany’s coal plants along the Elbe and Rhine faced similar constraints. Europe’s energy security now depends on water availability in ways that current infrastructure planning hasn’t fully internalized.

In northern Italy’s Po River basin, chemical and manufacturing plants have curtailed production during extended dry periods. These aren’t theoretical future risks—they’re present-day economic frictions that compound annually.

Why the Old Infrastructure Model Is Broken

Europe’s water infrastructure represents a triumph of 20th-century engineering: vast Spanish reservoirs, intricate French canal networks, sophisticated German distribution grids. But this infrastructure was designed for a different hydrological reality.

You cannot store what never arrives. This simple truth exposes the limits of traditional responses to water scarcity. When annual rainfall decreases and snowpack declines, expanding storage capacity merely spreads a diminishing resource more thinly. The reservoirs still run low; they just take slightly longer to do so.

Consider the economics. Large dam projects disrupt river ecosystems, displace communities, and require enormous capital with multi-decade payback periods—all while failing to address the fundamental supply deficit. Inter-basin water transfers simply relocate scarcity rather than resolving it, often creating political tensions between regions competing for the same diminishing resource.

The old model reflected a different logic: water management meant supply augmentation, not demand optimization. For a century, European systems operated on “predict and provide”—forecast demand growth, then build infrastructure to meet it. This worked when water was effectively unlimited. It fails when the resource base itself is contracting.

The question is whether doubling down on supply-side engineering, without fundamentally rethinking demand, makes strategic sense anymore. It’s a question that leads naturally to an uncomfortable comparison: what can Europe learn from places that have already confronted water scarcity as an existential challenge?

A Paradigm Shift in Water Management

Singapore’s approach offers a useful contrast, not because Europe should copy it wholesale, but because its strategic logic deserves attention.

With no natural aquifers and historic dependence on Malaysian water imports, Singapore faced existential insecurity. Rather than simply expanding conventional sources, the city-state redesigned its entire approach. NEWater—purified recycled wastewater—now provides 40% of current demand and is projected to meet 55% by 2060. Desalination contributes another 25%. An extensive network captures stormwater across two-thirds of the island, channeling it to reservoirs rather than allowing runoff to waste.

But infrastructure diversity is only half the story. Singapore prices water to reflect its strategic value, incorporating not just treatment and distribution costs but the price of future scarcity. Residential tariffs are structured progressively, making basic needs affordable while imposing higher costs on heavy consumption. Industrial users face incentives to recycle within their operations—the electronics and pharmaceutical sectors have developed closed-loop systems that minimize freshwater intake.

The crucial insight isn’t about copying specific technologies or policies. It’s about treating water as a strategic constraint requiring system-wide management, not just an engineering challenge requiring infrastructure. Supply, demand, pricing, and reuse operate within a unified framework rather than separate agencies optimizing for different objectives.

Europe doesn’t need Singapore’s exact solutions. But Europe does need that mindset: water scarcity demands comprehensive redesign of how societies produce, price, allocate, and reuse water, not merely incremental improvements to existing systems.

Continental Coordination and Governance

Europe’s water challenge is continental in scale. Its governance remains stubbornly fragmented.

Major river basins—the Rhine, Danube, Po, Tagus—cross multiple national borders, yet water allocation decisions remain primarily national or sub-national. Countries optimize for domestic interests, even when upstream withdrawals create downstream shortages. The result is uncoordinated policies that leave systemic risks unaddressed.

This fragmentation extends beyond international borders. Within countries, water governance divides among sectoral ministries—agriculture, energy, environment—plus regional authorities and local utilities, each with different priorities and limited incentive to coordinate.

- Agriculture ministries promote irrigation expansion.

- Energy ministries prioritize hydroelectric and thermal generation.

- Environment ministries focus on ecosystem health.

- Utilities concentrate on urban supply.

These objectives often conflict, yet few structures exist to adjudicate trade-offs at the basin level where hydrological reality operates.

The EU’s Water Framework Directive, adopted in 2000, established important principles for integrated river basin management. But implementation has been uneven, enforcement weak, and the directive lacks mechanisms to compel cross-border cooperation on allocation during scarcity. When reservoirs run low and rivers dwindle, countries revert to national decision-making, often at downstream neighbors’ expense.

What’s needed is governance commensurate with the challenge: a continental water coordination mechanism with authority to set allocation priorities during scarcity, establish common standards for pricing and reuse, coordinate cross-border infrastructure investment, and enforce basin-level sustainability targets.

This may sound politically ambitious. But Europe created a continental energy market, harmonized telecommunications regulation, and coordinates monetary policy across diverse economies. Water is no less strategic than energy, telecommunications, or currency. The question is whether political leadership will recognize this before crisis forces a more chaotic reckoning.

Policy Gaps and Sectoral Pressure

Agriculture accounts for 59% of total EU water withdrawals, rising to 75% during Mediterranean summers when irrigation demand peaks precisely as availability reaches its annual minimum. This isn’t inherently problematic—food production is essential—but it becomes untenable when agricultural water use is neither priced to reflect scarcity nor managed to prioritize the most economically valuable or nutritionally important crops.

In many regions, farmers pay only a fraction of the true cost of water delivery, and often nothing for groundwater pumped from private wells. Spanish greenhouse vegetables requiring intensive irrigation are grown for export to northern Europe while local aquifers deplete. Italian rice cultivation continues in the Po Valley even as the river reaches historic lows. French maize production expands in regions where summer rainfall is insufficient and groundwater is already over-extracted.

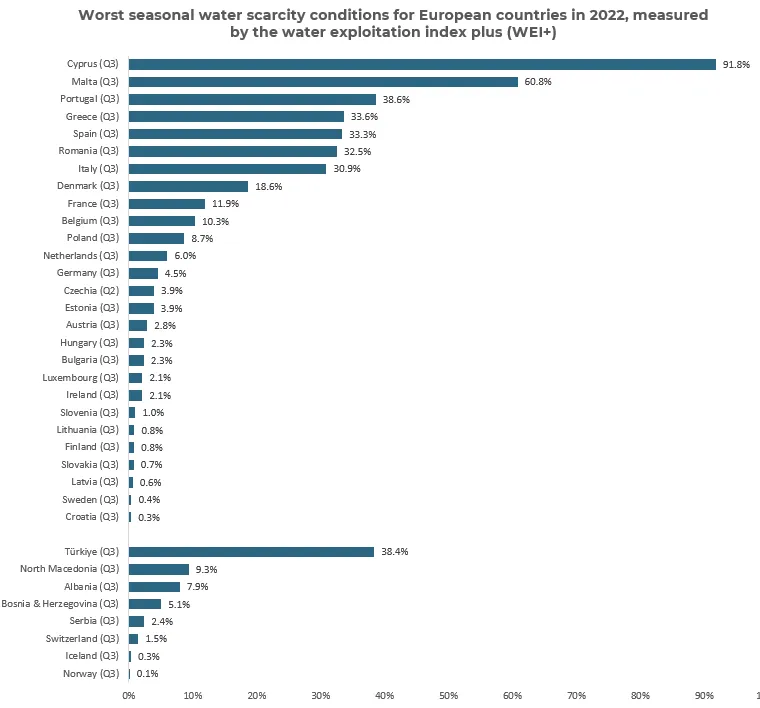

The 2022 data reveals the scale and distribution of this pressure. During the worst seasonal conditions, Cyprus and Malta experienced water exploitation rates exceeding 90%—meaning these countries were withdrawing nearly all available renewable freshwater. Spain, Belgium, and Italy all surpassed the 40% threshold marking severe stress. These aren’t uniformly distributed national challenges but concentrated seasonal crises that coincide precisely with peak agricultural demand.

Tourism adds seasonal pressure, particularly in Mediterranean coastal areas where summer visitor populations can double or triple the resident base, straining municipal systems exactly when natural supply is lowest. Industry, while more efficient than agriculture on a per-liter basis, is less flexible—manufacturing processes require reliable supply, and uncertainty can force production cuts or facility closures.

Despite the Water Framework Directive’s goal of achieving “good ecological status” for all water bodies, only 40% of surface waters currently meet this standard. The gap reflects not just inadequate pollution control, but fundamental conflicts between ecological sustainability and economic water use. Rivers over-extracted for irrigation cannot maintain healthy ecosystems. These aren’t problems that better pollution control can solve—they require rethinking how much water can be extracted without degrading the resource base itself.

Current policy approaches remain reactive and fragmented. Countries respond to drought emergencies with temporary restrictions but rarely implement long-term demand management. Sectoral policies—agricultural subsidies, energy planning, industrial permitting—are rarely integrated with water availability constraints.

Preparing for a Scarcer Future

Climate projections indicate the shift Europe is experiencing will intensify through 2030, 2050, and beyond. Summer precipitation in Mediterranean regions is expected to decline further. Extreme precipitation events will become more frequent, exacerbating the mismatch between availability and seasonal demand. Simultaneously, population growth in urban coastal areas will increase consumption pressure, and economic development in Eastern Europe will add industrial demand.

This trajectory leaves little room for complacency. The conventional approach—waiting for crises to force short-term responses—will become increasingly costly and disruptive. What’s needed is proactive risk management: anticipating constraints, investing ahead of need, and building institutional capacity to manage trade-offs before they become emergencies.

Healthy watersheds with intact forests, wetlands, and riparian zones provide natural water retention and filtration that engineered systems cannot replicate at comparable cost. Restoring degraded ecosystems isn’t merely environmental amenity—it’s water infrastructure. Similarly, managed aquifer recharge can rebuild groundwater reserves depleted by decades of over-extraction.

Water reuse technologies must shift from niche applications to mainstream infrastructure. Urban wastewater, currently treated and discharged to rivers or the sea, represents a reliable source independent of rainfall variability. With advanced treatment, this water can be reused for irrigation, industrial cooling, or even potable supply. Several Mediterranean cities have begun implementing reuse systems, but adoption remains limited by regulatory barriers, public perception challenges, and fragmented planning.

Pricing reform is perhaps the most politically sensitive but economically essential intervention. Progressive tariff structures can protect basic needs while discouraging waste. When water carries a meaningful price, users—farmers, industries, households—have reason to invest in efficiency, and markets can guide resources toward their most valuable applications.

Basin-level cooperation must become the norm. This means joint management authorities for shared rivers, with power to allocate water during scarcity based on transparent criteria rather than political bargaining. It means coordinated monitoring systems providing real-time data on availability and use. And it means dispute resolution mechanisms that prevent conflicts from escalating.

Final Throughts

Europe’s water crisis won’t end when the rains return. The water cycle that sustained European civilization for millennia has shifted, and it won’t shift back.

This reality demands a change in mindset—from managing abundance to managing scarcity, from engineering supply to orchestrating demand, from national optimization to basin-level cooperation. The infrastructure, pricing mechanisms, and governance institutions that served Europe well in the 20th century are inadequate for the 21st.

The economic stakes are considerable. Water scarcity already imposes friction costs on transport, energy, and industry—sectors critical to European competitiveness. These costs will multiply if Europe continues managing water as if the old baseline still applies. Conversely, countries and regions that innovate in water governance, invest in resilient infrastructure, and adopt integrated demand management will gain competitive advantage.

But the challenge also presents an opportunity. Europe has historically led in environmental regulation, clean technology, and institutional innovation. The continent that created transnational governance for steel and coal, then extended it to a single market and common currency, possesses the institutional capacity to coordinate water management at the necessary scale.

The hydrology has already changed. The question is whether Europe’s institutions, policies, and economic strategies will change with it—and how quickly. The choice is between proactive transformation and reactive crisis management. Between shaping Europe’s water future and being shaped by it.

Written by George Chanturia, Partner at Argo Advisory

Sources:

- Europe’s water crisis is much worse than we thought | National Geographic

- Water scarcity conditions in Europe | Indicators | European Environment Agency (EEA)

Argo Advisory | Published: November 2025